Agriculture

July 4, 2017

Published: 2002

The author of the following article is Salah Zaimeche BA, MA, Ph.D. of the “Foundation of Science Technology and Civilization.” For the full article, please use the link below: http://www.muslimheritage.com/topics/default.cfm?ArticleID=227

History books in schools usually convey the notion that the agricultural revolution took place in recent times in the form of rotation of crops, advanced irrigation techniques, plant improvements, etc. Some such changes took place only in the last couple of centuries in Europe and recently as well. Such revolutionary changes fed the increasing European population.

History books in schools usually convey the notion that the agricultural revolution took place in recent times in the form of rotation of crops, advanced irrigation techniques, plant improvements, etc. Some such changes took place only in the last couple of centuries in Europe and recently as well. Such revolutionary changes fed the increasing European population.

Windmill from the 7th Century- During the rule of the Second Caliph, Umar Ibn Al Khattab, 634-644 CE

Windmill from the 7th Century- During the rule of the Second Caliph, Umar Ibn Al Khattab, 634-644 CE

It also released vast numbers from the land and allowed agriculture to produce a capital surplus. That surplus was invested in the industry, thus leading to the industrial revolution of the 18th-19th century. This understanding is the accepted wisdom until one comes across works on Muslim agriculture and discovers that such changes took place over ten centuries ago in the Muslim world. These changes were the foundations of much of what we have today.

In particular, Watson, Glick, and Bolens show that breakthroughs were achieved by Muslim farmers and by Muslim scholars with their treatises on the subject. Thus, as with other issues, prejudice distorts history, and Muslim achievements of ten centuries ago have been covered up. This point was raised by the French scholar Charbonneau, who holds: “It is admitted with difficulty that a nation in a majority of nomads could have had known any form of agricultural techniques other than sowing wheat and barley.

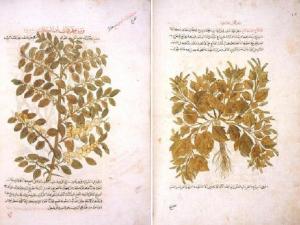

Tree herbal / botanical physiology

The misconceptions come from the rarity of works on the subject. If we bother to open up and consult the old manuscripts, so many views would be changed, so many prejudices will be destroyed.

The Agricultural Revolution

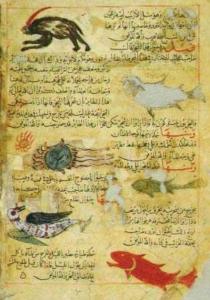

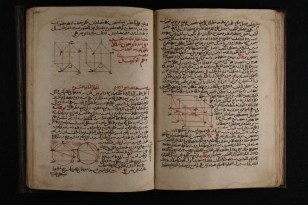

As early as the ninth century, a modern agricultural system became central to the Muslim land’s economic life and organization. The great Islamic cities of the Near East, North Africa, and Spain, Artz explains, were supported by an elaborate agricultural system. This system included extensive irrigation and expert knowledge of the most advanced agricultural methods in the world. The Muslims reared the most beautiful horses and sheep and cultivated the best orchards and vegetable gardens. They knew how to fight insect pests, use fertilizers, and be experts at grafting trees and crossing plants to produce new varieties.

Glick defines the Muslim agricultural revolution in introducing new crops, when combined with extension and intensification of irrigation, created a complex and varied agricultural system, whereby a greater variety of soil types were put to efficient use. Fields that had been yielding one crop yearly before the Muslims were now capable of producing three or more crops in rotation. Agricultural production responded to the demands of an increasingly sophisticated and cosmopolitan urban population by providing the towns with various products unknown in Northern Europe.

Herbal medicine

For Scott, the Spanish Muslims’ agricultural system was “the most complex, the most scientific, the most perfect, ever devised by the ingenuity of man.” “Such advancement of Muslim farming, according to Bolens, was owed to the adaptation of agrarian techniques to local needs and a spectacular cultural union of scientific knowledge from the past and the present, from the Near East, the Maghreb and Andalusia. A culmination subtler than a simple accumulation of techniques, it has been an enduring ecological success, proven by the course of human history.”

Fertilizers were used according to a well-advanced methodology, while a maximum amount of moisture in the soil was preserved. Soil rehabilitation was cared continuously for, and protecting the thick beds of cropped land from erosion was, according to Bolens, again, “the golden rule of ecology” and was “subject to laws of scrupulous, careful ecology.” For Scott, the success of Islamic farming also lay in the laborious enterprise. No natural obstacle was sufficiently formidable to check the business and industry of the Muslim farmers. He tunneled through the mountains; his aqueducts went through deep ravines, and he leveled with infinite patience and labored through the rocky slopes of the Sierra (in Spain).

The rise in agricultural land productivity and sometimes of agricultural labor was owed to the introduction of higher-yielding new crops and better varieties of former crops. More specific land use, which often centered on the new crops and through more intensive rotations with the new plants and the concomitant extension and improvement of irrigation, also led to an increase in productivity. The spread of cultivation into new or abandoned areas and the development of more labor-intensive farming techniques also provided a significant increase in productivity.

Waterwheel, Hamah, Syria

These changes, themselves, were positively affected by changes in other sectors of the economy: the growth of trade, enlargement of the money economy, increasing specialization of factors of production in all industries, and with the growth of population and its increasing urbanization.

From Andalusia to the Far East, from Sudan to Afghanistan, Irrigation remained central, “the basis of all agriculture and the source of all life.” ”The ancient systems of irrigation the Muslims became heirs to, were in an advanced state of decay, and ruins.” They repaired them and constructed new ones, besides devising new techniques to catch, channel, store, lift the water, and make ingenious combinations of available devices.

Spain – Andalucia – Granada – water gardens in the Alhambra Palace

All of the Kitab al-Filahat (book of agriculture), whether Maghribi, Andalusian; Egyptian, Iraqi; Persian, or Yemenite, Bolens points out, insist meticulously on the deployment of equipment and the control of water.

Water Management

Water, such a precious commodity in a more Islamically aware age, was managed according to stringent rules, waste of the resource banned, and the most severe economy enforced. Thus, in the Algerian Sahara, various water management techniques were used to make the most efficient use of the resource. The Foggaras, a network of underground galleries, conducted water from one place to the other over very long distances to avoid evaporation. Although the system is still in use today, the tendency is for over-use and waste of water. Still in Algeria, in the Beni Abbes region, in the Sahara, south of Oran, farmers used a clepsydra to determine water use duration for every user in the area. This clepsydra regulates with precision, night and day, the amount going to each farmer, timed by the minute, throughout the year and taking into account seasonal variations. Each farmer is informed of his turn’s timing and summoned to undertake necessary action to ensure adequate supply to his plot. In Spain, the same strict management was in operation. The water conducted from one canal to the other was used more than once. The quantity supplied accurately graduated; distributing outlets were adapted to each soil variety, two hundred and twenty-four of these, each with a specific name. All disputes and violations of laws on the water were dealt with by a court whose judges were chosen by the farmers themselves; this court, named The Tribunal of the Waters, sat on Thursdays at the principal mosque door. Ten centuries later, the same tribunal still sits in Valencia but at the entrance of the cathedral. Interesting…

The Loss of Ecological Balance

“With a deep love for nature, and a relaxed way of life, classical Islamic society,” Bolens concludes, “achieved ecological balance, a successful average economy of operation, based not on theory but the acquired knowledge of many civilized traditions.” She recognizes colonialism, which subsequently and severely upset the traditional agricultural balance to increase profitability for the colonizers. The decline of agriculture and (deleted words) other aspects of Islamic civilization had begun with the various invaders, from the Crusaders to the Mongols, the Banu Hillal to the Normans, and Spain’s conquistadors in the West. Such invasions caused the ruin of irrigation works, destroyed permanent crops, closed down trade routes, and caused farmers to flee.

The Muslim farmers also became overtaxed by their new masters in Christian Spain and Sicily and were exterminated in those countries. Their system perished with them.

The Muslim farmers also became overtaxed by their new masters in Christian Spain and Sicily and were exterminated in those countries. Their system perished with them.

The later colonizers, the French, only finished off whatever was left. No better place to see that than in Algeria, where the French, on arrival in 1830, found a much greener country than the one they left 130 years later and a population living more or less in harmony with its environment. In their devastation wars against Algerian resistance, the French destroyed the garden rings that surrounded towns and cities, cutting trees and orchards. After that, they deforested whole regions to exploit timber and took all fertile lands from their Muslim owners, forcing them to reside in arid areas and forests’ vicinity, causing their degradation.

Later, during the war of independence 1954-62, the French set ablaze millions of acres of forest lands. They then departed, leaving a legacy from greenery to bareness and hostility from which the Algerians have not yet recovered.

Recommended Posts

Women’s Rights to Own Property

January 20, 2018

Navigation

January 20, 2018

Algebra

July 4, 2017