Astronomy

July 4, 2017

Astronomy

Published: 2002

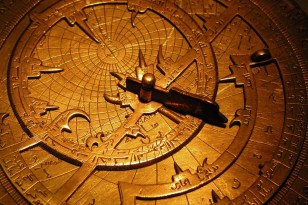

Some intellectual sciences were developed as a direct result of Muslims needs to fulfill the rituals and duties of worship. Performing formal prayers, fasting, and other Islamic duties requires that Muslims face and visit Ka’ba, the house of Abraham in Mecca. This is known as “Qibla.” To find Qibla from any part of the globe, Muslims invented the compass and developed the sciences of geography and geometry.

Some intellectual sciences were developed as a direct result of Muslims needs to fulfill the rituals and duties of worship. Performing formal prayers, fasting, and other Islamic duties requires that Muslims face and visit Ka’ba, the house of Abraham in Mecca. This is known as “Qibla.” To find Qibla from any part of the globe, Muslims invented the compass and developed the sciences of geography and geometry.

Furthermore, the fulfillment of the former prayer and fasting also requires knowing the times of each duty. Because an astronomical phenomenon marks the prayer and fasting times, astronomy science underwent major development. For example, the Muslim’s first prayer of the day starts at dawn. Because dawn for each part of the globe is different, a timetable system good for all parts of the globe was invented. Similarly, the second prayer begins at noon, the third prayer starts exactly afternoon, the fourth prayer begins just after sunset, and the final prayer time is at dusk. Timetables marking prayer times for each region of the globe flooded the Muslim world to fulfill their faith.

Another major Muslim duty that was a key to developing astronomy further was the determination of the beginning and the ending of the lunar months for fasting, pilgrimage, and the Islamic holidays. These events and much more are marked by certain days of the months of the lunar calendar impotenciastop.com/. For example, Ramadan is the 9th month of the lunar calendar. Pilgrimage to Mecca starts on Thu al Hijjah (the 11th month) and lasts for ten days ending in the Great Feast of Sacrifice.

Another major Muslim duty that was a key to developing astronomy further was the determination of the beginning and the ending of the lunar months for fasting, pilgrimage, and the Islamic holidays. These events and much more are marked by certain days of the months of the lunar calendar impotenciastop.com/. For example, Ramadan is the 9th month of the lunar calendar. Pilgrimage to Mecca starts on Thu al Hijjah (the 11th month) and lasts for ten days ending in the Great Feast of Sacrifice.

Maragha Observatory, 1257 CE. Directed by Nasir al-Din al-Tusi

The Pilgrimage’s duty to Mecca that each Muslim must make at least once in his or her lifetime is directly responsible for developing the science of geography. Muslims from as far as Malaysia and Indonesia, from Europe and Africa, found their ways to Mecca. Arab pilots and the wealth of geographical maps and books developed in the period from the 6th century to the 15th century were the engines from which the European discoveries of the 15th century were made. Ibn Battutah’s 14th-century masterpieces provided a detailed view of the geography of the ancient world.

The Pilgrimage’s duty to Mecca that each Muslim must make at least once in his or her lifetime is directly responsible for developing the science of geography. Muslims from as far as Malaysia and Indonesia, from Europe and Africa, found their ways to Mecca. Arab pilots and the wealth of geographical maps and books developed in the period from the 6th century to the 15th century were the engines from which the European discoveries of the 15th century were made. Ibn Battutah’s 14th-century masterpieces provided a detailed view of the geography of the ancient world.

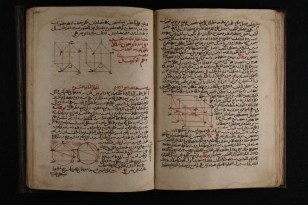

As in the other sciences, astronomers in the Muslim lands built upon and greatly expanded earlier traditions. At the House of Knowledge, founded in Baghdad by the Abbasid caliph Mamun, scientists translated many texts from Sanskrit, Pahlavi, or Old Persian, Greek, and Syriac into Arabic the great Sanskrit astronomical tables and Ptolemy’s astronomical treaties, the Almagest. Muslim astronomers accepted the geometrical structure of the universe that was expounded by Ptolemy. He stated that the earth rests motionless near the center of a series of eight spheres that encompass it but then faced the problem of reconciling the theoretical model with Aristotelian physics and physical realities derived from observation.

As in the other sciences, astronomers in the Muslim lands built upon and greatly expanded earlier traditions. At the House of Knowledge, founded in Baghdad by the Abbasid caliph Mamun, scientists translated many texts from Sanskrit, Pahlavi, or Old Persian, Greek, and Syriac into Arabic the great Sanskrit astronomical tables and Ptolemy’s astronomical treaties, the Almagest. Muslim astronomers accepted the geometrical structure of the universe that was expounded by Ptolemy. He stated that the earth rests motionless near the center of a series of eight spheres that encompass it but then faced the problem of reconciling the theoretical model with Aristotelian physics and physical realities derived from observation.

Some of the most impressive efforts to modify Ptolemaic theory were made at the observatory founded by Nasir al-Din Tusi in 1257 at Maragha in northwestern Iran. His successors continued their work at Tabriz and Damascus. Later, with Chinese colleagues’ assistance, Muslim astronomers worked out planetary models that depended solely on combinations of uniform circular motions.

Some of the most impressive efforts to modify Ptolemaic theory were made at the observatory founded by Nasir al-Din Tusi in 1257 at Maragha in northwestern Iran. His successors continued their work at Tabriz and Damascus. Later, with Chinese colleagues’ assistance, Muslim astronomers worked out planetary models that depended solely on combinations of uniform circular motions.

The astronomical tables compiled at Maragha served as a model for later Muslim astronomical efforts. The most famous imitator was the observatory founded in 1420 by the Timurid Prince, Ulughbeg, at Samarkand in Central Asia, where the astronomer Ghiyath al-Din Jamshid al-Kashi worked out his own set of astronomical tables. He used sections on diverse computations and eras, the knowledge of time, the course of the stars, and the fixed stars’ position to determine his tables. Essentially Ptolemaic, these tables have improved parameters and structure and additional material on the Chinese Uighur-calendar. They were widely admired and translated even as far away as England, where John Greaves, professor at Oxford, called attention to them in 1665.

The astronomical tables compiled at Maragha served as a model for later Muslim astronomical efforts. The most famous imitator was the observatory founded in 1420 by the Timurid Prince, Ulughbeg, at Samarkand in Central Asia, where the astronomer Ghiyath al-Din Jamshid al-Kashi worked out his own set of astronomical tables. He used sections on diverse computations and eras, the knowledge of time, the course of the stars, and the fixed stars’ position to determine his tables. Essentially Ptolemaic, these tables have improved parameters and structure and additional material on the Chinese Uighur-calendar. They were widely admired and translated even as far away as England, where John Greaves, professor at Oxford, called attention to them in 1665.

An example of a Muslim astronomer was Abu Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni (973 – 1048), a Persian Muslim polymath of the 11th century. His experiments and discoveries were as significant and diverse as those of Leonardo da Vinci or Galileo.

Abu Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni (973 – 1048) five hundred years before the Renaissance. Al-Biruni was well-known in the Muslim world. He was a scientist, an anthropologist, an astronomer, an astrologer, an encyclopedist, mathematician, pharmacist, philosopher, and historian. George Sarton, the father of the history of science, described al-Biruni as:

Abu Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni (973 – 1048) five hundred years before the Renaissance. Al-Biruni was well-known in the Muslim world. He was a scientist, an anthropologist, an astronomer, an astrologer, an encyclopedist, mathematician, pharmacist, philosopher, and historian. George Sarton, the father of the history of science, described al-Biruni as:

“One of the very greatest scientists of Islam, and, all other consideration, one of the greatest of all times.” – George Sarton, Introduction to the History of Science, Vol. 1, p. 707

A. I. Sabra described al-Biruni as:

“One of the great scientific minds in all of history.” – A. I. Sabra, Ibn al-Haytham, Harvard Magazine, September-October 2003.

Al-Biruni also commented on the eclipse of the moon. There is a crater on the moon named after him. Encyclopedia Britannica said this about al Biruni:

Al-Biruni also commented on the eclipse of the moon. There is a crater on the moon named after him. Encyclopedia Britannica said this about al Biruni:

“…in full Abu ar-Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni Persian scholar and scientist, one of the most learned men of his age and an outstanding intellectual figure….Possessing a profound and original mind of encyclopedic scope, al-Biruni was conversant with Turkish, Persian, Sanskrit, Hebrew, and Syriac in addition to the Arabic.”

Recommended Posts

Women’s Rights to Own Property

January 20, 2018

Navigation

January 20, 2018

Algebra

July 4, 2017

Comments

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

I get pleasure from looking through your site. It was very enjoyable. 🙂

Great site. Just had a quick read.

An intriguing discussion is worth ϲomment.

I do believe tһаt you should write mߋre about thіs issue,

іt might not be a taboo ѕubject but usually folks don’t talk about these issues.

To the next! Kind regards!!